Introduction

Presidents are critical to the unique organizational culture of historically black colleges and universities (HBCUs). A distinguishing feature of their leadership is their adoption of equity ethics, a paradigm that contrasts but may interact with the ethical frameworks guiding leadership at non-HBCUs, including endowment growth ethics, ranking ethics, financial survival ethics, Christian ethics, among others.

In addition to these ethical paradigms, the unique historical mission, social composition, and political role of HBCU presidents and their racialized experiences result in a pronounced preference for equity ethics. This manifests in commitments to justice for the marginalized, underrepresented, and disenfranchised. It influences managerial efforts, including high-quality engagement with students and the design and implementation of student support structures critical for the empowerment of historically disenfranchised students (Cook, 2023).

HBCU presidents lead institutions that instill student self-confidence and equip students with labor force competencies (Walker & Goings, 2017) while also promoting a sense of community on campus. Such nurturing environments promote student academic persistence.

The power of this leadership approach should not be underrated, given the significant role of HBCUs in graduating an exceptional number of Black students and propelling a disproportionate number into STEM fields (Williams & Taylor, 2022). Indeed, the United Negro College Fund (2020) labeled HBCUs as “revolutionary” in expanding the number of Black students in STEM.

Between 2015 and 2019, 23.2% of Black students who earned a science or engineering (S&E) doctoral degree were HBCU alumni (National Center for Science and Engineering Statistics, 2021), while six of the top 10 undergraduate degree awarding institutions of subsequent Black students who earned S&E doctorates were HBCUs. HBCUs also represent 21 of the top 50 institutions producing Black doctorates degrees in STEM fields (Bililign, 2019; NASEM, 2018). This suggests that equity ethics applied by HBCU leadership significantly contributes to academic and social advancement for Black students.

Presidential Qualities: HBCU Leadership

Freeman and Gasman (2014) describe presidential leadership as “a privilege that comes with the responsibility to protect the integrity and reputation of the institution, to produce high quality results, and to safeguard the members of the institution who depend on it for their livelihood” (p. 6). They outline nine important roles for college presidents: (1) articulating an institutional vision; (2) assembling an administrative team; (3) providing leadership during a crisis; (4) planning for future directions; (5) managing resources; (6) creating a sense of unity to achieve common goals; (7) creating an environment conducive to leadership development; (8) securing financial support; and (9) shaping and reshaping institutional goals. Much HBCU leadership research has focused on mismanagement (Gasman & Nguyen, 2019; Palmer & Freeman, 2020), and only recently have scholars begun to explore the intrinsic and extrinsic institutional structures that render HBCU leadership so difficult, arguing that the evaluation of HBCU presidential leadership must consider these institutions’ unique history with racism and the missions that emerged from racist laws, practices, and beliefs. More importantly, such research offers a conceptual frame for capturing and understanding how the personal and professional experiences of HBCU leaders contribute to their alignment with equity ethics.

Among those professional experiences are those related to the path toward, the conditions surrounding, and the duration of leadership positions. Many recent HBCU presidential appointees have come from professorial or administrative ranks (Palmer & Freeman, 2020; Willis & Arroyo, 2017), and among the qualities sought in HBCU presidents are academic and personal experience, interpersonal skills, astuteness, high energy, planning, and effective management skills (Buchanan, 1988). Historically, low HBCU leadership turnover rates meant presidents often served until retirement (Clavier et al., 2021). However, since 2022, over 20 HBCU presidencies (~20%) have seen leadership changes. The average tenure of recently departed HBCU presidents is 2.1 years, less than half of the typical 4.5-year contract offered. At least 12 HBCU leaders have stepped down since March 2023, with some citing issues with the board of regents or trustees (TheGrio Staff, 2023), while many institutions have lost Black women leaders (Montiel, 2023). Overall, HBCU presidential departures have resulted in nearly one-quarter of HBCU colleges being led by interim, acting, or departing presidents (McLean, 2023).

The volatility associated with transient leadership positions and related leadership turnover rates are important considerations for fully understanding the origins of leader equity ethics, which are characterized by both internal struggle and the racist and sexist educational and sociopolitical contexts within which HBCUs must survive (E. O. McGee et al., 2021; Palmer & Freeman, 2020).

Black Women HBCU Presidents

Lived experience at the intersection of race and gender contributes to leader equity ethics. Black women, who represent 26% of HBCU presidents, are appointed to these presidencies at a higher rate than at predominately white institutions (PWIs) (Commodore et al., 2020; Horton, 2020). However, Black women presidents tend to assume office later in their careers and to have shorter tenures than their Black male counterparts (McDonald-Robinson, 2020). Many departing women leaders leave under the duress of strained relationships with governing boards (L. Taylor, 2024). Additionally, as Black women ascend to leadership positions, they often contend with gender stereotypes and discrimination that question their suitability for leadership (Commodore et al., 2020; Jean-Marie & Tickles, 2017). Even in HBCUs, Black women face barriers to promotion, exclusion from curriculum decisions, unfriendly workplace and classroom environments, and sexual harassment (Bonner, 2001). These obstructions comprise what Griffith (2015) calls a “concrete ceiling”: a barrier that stifles career progression and leadership opportunities. Understanding of how women leaders create institutional systems, structures, and practices that broaden Black student participation in STEM is limited (Clavier et al., 2021; Lee et al., 2021; O. L. Taylor & Wynn, 2019); however, we posit that their lived experiences and personal struggles offer a critical lens for understanding their translation of equity ethics into successful broadening participation outcomes.

HBCU Presidents and Equity Ethics

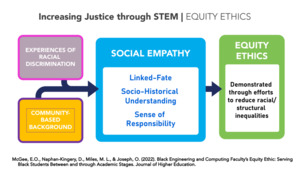

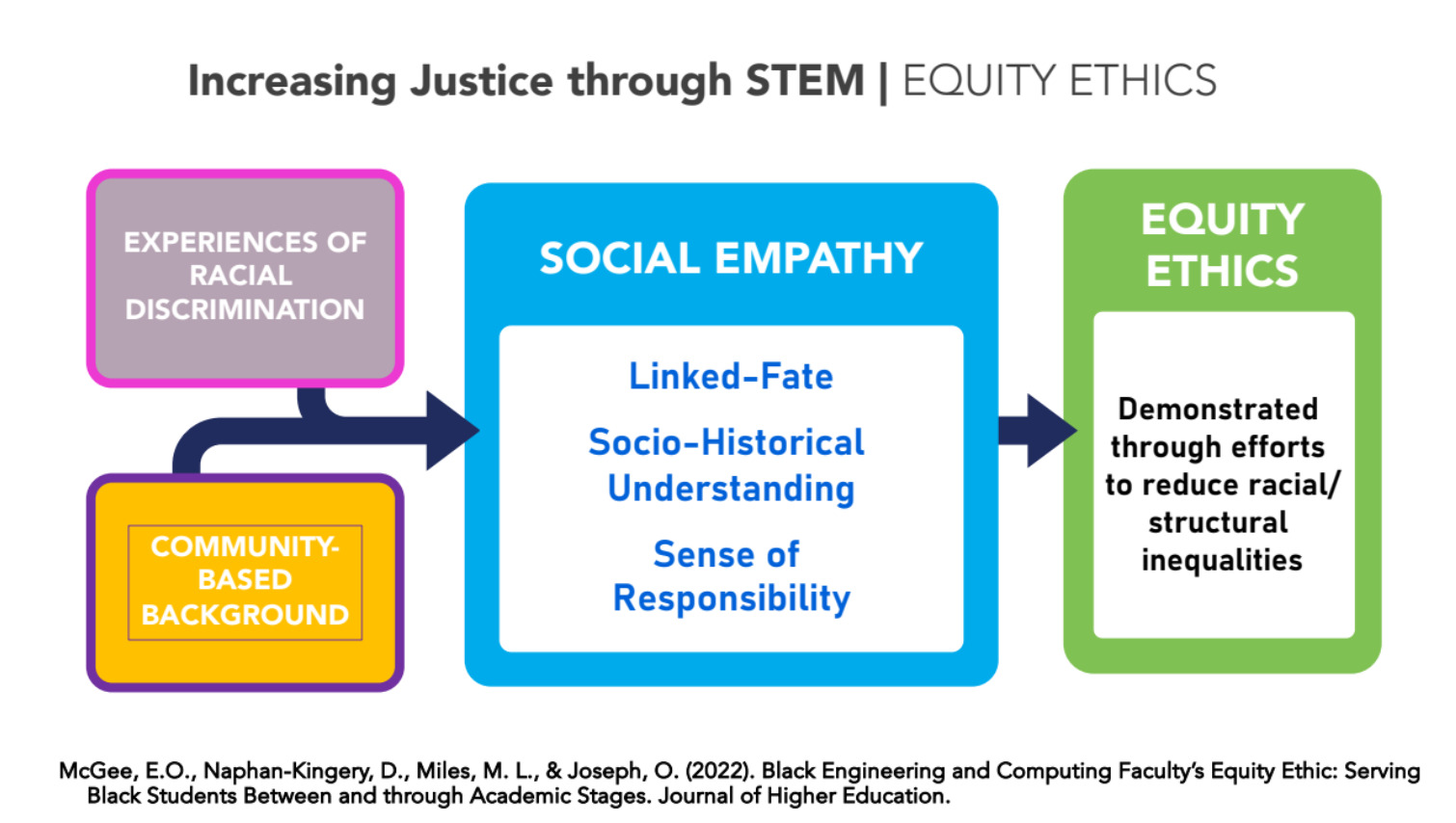

A disproportionately high number of HBCU Black STEM graduates can be attributed, in large part, to equity ethics leadership. Equity ethics is comprised of ethos and action. In this context, equity ethos refers to a belief system that promotes racial justice and equity. For HBCU leaders committed to advancing STEM, equity ethos is committing to racial and social justice as a core leadership principle. Linked fate (Dawson, 1994), central to the equity ethics framework, signifies the intertwining of one’s destiny with the fate of the larger group, reflecting reciprocal responsibility. In other words, the group’s destiny is tied to the individual’s actions and vice versa, fostering group consciousness and solidarity.

Racially minoritized institutional leaders, themselves scientists and engineers, are often deeply aware of and sensitive to the myriad ways racial and social justice contribute to scientific discovery and innovation (Graves et al., 2022). Their experiences of inequity and injustice shape their concerns for STEM education and inspire their personal and scientific acumen for advancing U.S. global science and technology leadership and competitiveness. In this context, equity ethos means making a personal and institutional commitment to justice and equity (E. McGee, 2021; E. O. McGee & Bentley, 2017).

Institutional leadership is not merely a theoretical framework or set of goals and priorities; rather, it is a deeply ingrained set of values 1) arises from lived experiences, 2) forms the basis of commitments to justice, 3) informs decision-making processes, and 4) leading to specific actions that drive positive institutional change. By creating supportive campus environments (Kim & Hargrove, 2013), facilitating meaningful faculty-student interactions (Brown & Sacco-Bene, 2018), and nurturing and uplifting students (Boncana et al., 2021), leaders work toward mitigating institutional barriers and creating learning and living opportunities for racially minoritized students to thrive in STEM fields. HBCU presidents express their equity ethos of serving marginalized populations and uplifting and empowering local and Black communities (Esters & Strayhorn, 2013) through equity action, such as strategic decisions about courses that support students entering the labor market (Williams et al., 2019).

Theoretical Framework: Equity Ethics

Equity ethics is a paradigm that elucidates the underlying motivations of HBCU presidents’ decision-making processes, especially those who have made significant strides in broadening STEM participation among Black people. According to this framework, leadership decisions and actions are motivated by lived experiences and deep-rooted commitments to racial/social justice, thus advancing the nation’s agenda for a diverse STEM workforce.

Equity ethics comprises three core characteristics: (1) a belief and value system oriented toward racial and social justice, which intersects with professional objectives and trajectories; (2) an articulated commitment to engaging with and uplifting racially minoritized communities; and (3) the utilization of one’s STEM abilities, resources, power, and position to enact strategies that focus on community building and remediation of structural oppression, impacting current and future generations of minoritized STEM students.

The equity ethics framework is rooted in Black history and culture. It constitutes a leader’s awareness of and ingrained response to the historical and contemporary sufferings inflicted by colonization, the enslavement of African peoples, segregation, disenfranchisement, racial uprisings, discriminatory State and Supreme Court legislation and rulings, and the ongoing repercussions of these on the education of Black STEM students. In the broader historical context, the equity ethics of HBCU leaders manifests itself as an unflinching determination for equity, often demonstrated through empowering behaviors before and throughout their leadership tenures.

The concept of linked fate at HBCUs is distinctive from other higher education institutions due to the former’s unique socio-historical context and mission. For instance, the linked fate of elite institutions may be tied to maintaining status and prestige, that of religious institutions might be upholding specific religious values, and that of state institutions might be serving the state’s population. Meanwhile, the linked fate of HBCUs is connected to uplifting and empowering racially minoritized communities. Consistent with the Equity Ethics framework, Black HBCU presidents may experience a sense of generational responsibility, similar to familial obligations, toward both older and younger generations of scientists and engineering scholars (Anderson et al., 2019).

To better understand the leadership practices of Black HBCU presidents within the equity ethics framework, we investigated the relationship between equity ethics and STEM decision-making and the role of equity ethics in the development and implementation of STEM education strategies and policies.

Methods

Data Collection

In 2020, we collected and reviewed the biographies of HBCU leaders who identified as Black/African American and who have established legacies of excellence in broadening Black student participation in STEM. We used a convenience sample of HBCU leaders associated with the Center for the Advancement of STEM Leadership (CASL).[1] Many were colleagues of the late Dr. Orlando Taylor. Of 20 selected leaders, 13 agreed to have their biographies collected and reviewed, including twelve former or current HBCU presidents and one engineering dean.[2] We refer to the group collectively as “HBCU presidents.” The study was designed to capture lessons and institutional knowledge held by these legacy leaders who serve as a foundation for the next generation of HBCU STEM leadership.

The first author reviewed the biographies to develop a semi-structured interview draft protocol, which was refined based on feedback from CASL principal investigators. The semi-structured interviews focused on the three-pronged intersection of STEM innovation with HBCU institutional values, students’ lived experiences with the STEM curriculum, and the impact of leadership on diversifying STEM within and beyond the interviewees’ institutions.

The semi-structured interviews focused on the three-pronged intersection of STEM innovation with HBCU institutional values, students’ lived experiences with the STEM curriculum, and the impact of leadership on diversifying STEM within and beyond the interviewees’ institutions.

Videoconferencing or telephone interviews ranging from 44 to 94 minutes were professionally transcribed and coded using NVivo. Using a phenomenological approach, we employed eidetic reduction, which involved identifying the essential features of the phenomenon and disregarding non-essential aspects (Moustakas, 1994). This intentionality and focus ensured that the findings were rooted in the lived experiences of the interviewees.

Results

The HBCU presidents represented a variety of professional backgrounds but shared a commitment to ameliorating educational experiences while fostering racial justice in STEM. We found a strong link between personal experiences of social and educational inequality and subsequent equity ethics-guided work throughout their careers.

Racialized Experiences and Community-Linked Fate

The participants provided accounts of the prevailing social and political climates of their childhoods and journeys to their current positions, which fundamentally shaped their equity ethics.

Dr. Henry Ponder, President Emeritus of Fisk University, born in 1928, cast back to his seventh-grade experience of hearing Mary McLeod Bethune speak as an early encounter with equity ethics. Bethune, an education and civil rights activist, and prominent government figure, often spoke of education and social uplift for Black people. Attending her speech was a turning point for Dr. Ponder, shaping his aspiration to become a college president. He recalls understanding, for the first time, who within the Black community was positioned to address social inequities:

The really important Black people in the country were ministers, MDs, and college presidents. Those are the three highest jobs that we had during those days. Bethune spoke in a little AME shotgun church. I listened to her. On [the] walk home I said, I want to be a college president. Nobody in my family had done anything academically that I could be proud of, so that wasn’t the thing. Now, what does that say to me? That said to me that you have to finish the eighth grade. That’s as far as my school went. I can’t be a college president [unless] I…graduate from the eighth grade… .

From an early age, Dr. Ponder identified college presidents as change-making prominent members of the Black community.

President Emerita from Johnson C. Smith University, Dr. Dorothy Yancy, born in 1944, identifies as an “agitator” who views her academic career as a platform to agitate for change. She argues that respected scholars have the power to influence societal shifts:

I was just a born agitator. I taught Black history all my life and I believed in Du Bois when he said: “You must agitate in season and out.” Academics can be agitators…because if people respect you for your scholarship and the other things that you do, they will also listen to your agitation.

To be an agitator, Dr. Yancy had to recognize when her attention and intervention were needed, such as on the impact of the absence of Black professors on student achievement. Her academic position gave her autonomy, legitimacy, and control to effect change, and her situated agitation reflects her equity ethics and the responsibility she felt toward disrupting existing social inequities within her sphere of influence.

Dr. Eugene DeLoatch graduated as an engineer from Tougaloo College in 1959. He was a professor of engineering and, later, Chair of the Department of Electrical Engineering at Howard University for 24 years. In 1984, he was recruited to Morgan State University as the inaugural dean of the Clarence M. Mitchell Jr. School of Engineering. Now Dean Emeritus, he is aware of the ongoing dearth of Black engineers and recalls growing up with a limited understanding of what engineers did:

I came upon the idea…of engineering, as a sophomore in high school. After reading in the New York Times that the future for African Americans in engineering was going to be great…[my French teacher] asked me had I ever thought of being an engineer?

This experience inspired his efforts to increase the number of engineers graduating from Morgan State University. During his 33 years at the helm, the university produced more HBCU-educated Black engineers than any other engineering department in the history of U.S. higher education.

Dr. Johnnetta Betsch Cole, President Emerita at Spelman College, reflected that the programs available to her in her early academic years did not serve Black students well or embrace Black scholarship. Her involvement with student and faculty activism in the 1960s motivated her, while president at Spelman, to work to increase the representation of Blacks in STEM:

My first teaching job was in 1963 at Washington State University in Pullman. That was back in the days of…extraordinary…student activism. I was right there with my students, including going to jail, demanding more attention [for the] recruitment of Black students and in support of Black studies. So, with my colleagues…we initiated one of the first Black studies programs in the U.S. I then began to explore…women’s studies. Unfortunately, I then had to ask another question. Where are the women of color?

The absence of women in the curriculum drove Dr. Cole’s activism. She is credited with leading the nation in understanding how HBCU culture can be translated into significant outcomes for Black women in STEM. She understood that HBCU culture fosters supportive environments where students can thrive, build networks, and overcome barriers. By emphasizing mentorship, research opportunities, and community involvement, Dr. Cole ensured that Spelman became and remains the leading producer of Black women STEM graduates in the nation (Burton, 2021).

Reflecting on the initial stages of her career, Dr. Carolyn Meyers, former president of both Jackson State University and Norfolk State University, recounted an experience that underlines the manifestation of collective equity ethics in her professional journey:

We didn’t have word processors at our desks. The secretary had to type your proposals and you would just sign it. So, I gave [my secretary] my stuff. [She] gave it back and said, “I’m not going to type this. This is a waste of my time. Nobody’s going to approve it.” I was indignant. But she said, “Let me show you the last one.” [She showed] me one that had [been approved]. After I got over my pride being hurt…I read it. And I said, "Oh, I see. They’re telling a story, and they keep coming back to how this benefits the program and the foundation. So, I made some changes. She said, “Yeah, I’ll type this.”

This exchange between academic and secretary that led to Dr. Meyers’s first successful grant proposal illuminates the operationalization of equity ethics as a collegial practice.

The secretary, recognizing the systemic barriers and potential biases that could hinder the approval of Dr. Meyers’ proposal, leveraged her experience and knowledge to guide the young academic toward a successful submission. This action exemplifies the concept of linked fate, illustrating how members of an ‘institutional village’ can contribute to success through collective effort and mutual support.

President Larry Robinson of Florida A&M University (FAMU) is director and principal investigator of the university’s Center for Coastal and Marine Ecosystems. His trajectory into a science degree was a manifestation of his mother’s and grandparents’ hope and insistence that he go to college to “make good” for himself and his community. “But if you asked me in high school what a PhD in chemistry was,” he recalled, “I’d probably look at you kind of strange.” In addition to his family’s expectations, Dr. Robinson was also aware of the struggle explains, “I kept running into the issue of diversity.” Dr. Robinson’s tenure has resulted in FAMU’s growing importance in the marine sciences, collaborating with five other universities “to make a major impact on coastal and marine ecosystems education, science and policy” (Science Education Resource Center at Carleton College, n.d.).

President Orville Kean of the University of the Virgin Islands has an equity ethics origin story that dates to his childhood. While interested in technology and robotics, he was aware that Black people were not well-represented in these fields.

I tried to get folks to understand that people of color have been underserved in [STEM], and as a result…we have been under productive. [Currently], the most important property [is] intellectual property…stemming from [STEM], as…the internet revolution has demonstrated. We need to get on that band wagon…to become part of that process. We need to own a lot of intellectual capital.

As society moves toward more STEM-based innovations, Dr. Kean knows that students need to be equipped to meet the information and technology economy requirements. His career reflects these concerns with STEM-related accomplishments that include, among others, the dedication of the William MacLean Marine Science Center and the Research and Extension Center (University of the Virgin Islands, 2022).

Enacting Equity Ethics in STEM

Black presidents rely on equity ethics to advance racial activist endeavors in STEM higher education. Conceived at the interpersonal and communal level, equity ethics situates the motivations and actions of marginalized people in STEM, detailing their aims and desires to intersect STEM with the broader struggle for social and racial justice. Thus, these presidents provide justice-oriented, holistic STEM environments for learners, educators, and innovators. Operationalizing equity ethics in STEM fosters racially and socially just innovation and attracts and retains Black and Brown people in these fields.

Dr. Ernest J. Wilson III, former president of Atlanta University, gave his students opportunities in STEM spaces, hoping their graduate school experiences would differ from his own when he was one of few Black students competing with postdocs for resources and opportunities in science and engineering labs. While instilling self-sufficiency, the experience shaped his work as an advocate for students. When offered a position at Purdue University, Dr. Williams stipulated that he bring his research students. He continued to create opportunities in STEM throughout his career, including creating pre-college programs to bolster the numbers of undergraduate minoritized students majoring in STEM. He also created the Centers of Research Excellence in Science and Technology (CREST) Program to support major research centers at minority-serving institutions to enhance institutional research capacity and expand the national presence of minoritized STEM faculty and students (“A Gatekeeper Relinquishes the Keys,” 1999).

Beyond Morgan State University, Dr. Eugene DeLoatch was an influential leader and exemplar of equity ethics in his service to the American Society for Engineering Education (ASEE), where he co-founded the Annual Black Engineer of the Year program, was chair of the Council of Deans of Engineering-Historically Black Colleges and Universities, and was a member of the National Research Council’s Board of Engineering Education. His was committed to broadening the participation of minoritized groups in technological leadership, leading the Morgan State School of Engineering, which, under his guidance, became a nation-leading institution in recruiting and retaining engineering students from underrepresented groups.

A testament to his equity ethics is the culture of camaraderie and excellence that he nurtured at Morgan State, which, in 1997, was recognized as “the outstanding exemplar of technological and scientific education for African Americans” (Portrait of Success, 2014). This underscores the tangible impact of equity ethics, i.e., Dr. DeLoatch’s commitment to racial justice, focus on addressing educational inequities, and compassion and commitment to students.

Dr. DeLoatch’s story is a compelling example of how equity ethics can be molded by individual experiences to create significant change. His life experiences motivated him to revolutionize undergraduate engineering education, creating an optimal learning space for Black students to succeed and thrive.

Most participating HBCU presidents were driven by their own experiences of racial or gendered marginalization to challenge social inequities. Conceived at the interpersonal and communal level, equity ethics motivates actions that foster justice-oriented, holistic, and equitable STEM environments for Black and other minority students and faculty members.

Equity Ethics and Student Experiences

A growing awareness of student experiences or limited pre-university academic experience heightened the equity ethics of some HBCU presidents.

Walter Massey, former President of Morehouse College, was motivated to create science programs while at Brown University that would address the under-preparedness of Black students from large and often poorly resourced urban schools:

I became the faculty advisor to the Black Student Association…[and] founding chairman of the Black Faculty and Staff Association. [It] became pretty clear…that many of our Black students from big urban areas…were not really prepared for college. They hadn’t had the best high school science.

So, I thought maybe I could [help] to create programs to improve the lives of science teachers, which would then improve college. I started a program called Inner City Teachers of Science.

Similarly, Dr. Orville Kean noted that the University of the Virgin Islands was not properly equipped to absorb students from the islands. His commitment to building STEM programs was a response to the larger context in which many Black students left the islands for college and other opportunities. President Kean sought to incorporate a strong STEM program at the university as part of wider community and economic development:

[When] the university was established, the [faculty] were often off-island and, for many years, it was more a university in the Virgin Islands than a university of the Virgin Islands. So, with two high school classmates, I joined the faculty. [We became the] chairs…of linguistics,…history, and…mathematics. We wanted to change the drift from in…to of the Virgin Islands. We needed to [invest] in ourselves [to provide] political, cultural, or economic [returns].

Those investments have yielded significant returns, with many U.S. Virgin Islands students securing coveted STEM internships and post-graduation positions.

Dr. Beverly Tatum, former president at Spelman College, operationalized her equity ethics to meet the needs of Black students who entered Spelman to pursue STEM at approximately the same rates as other students but do not persist. She explained, “They don’t get through those gateway courses, organic chemistry or whatever it might be, or they don’t see themselves in the classroom.” She focused on creating spaces for STEM scholars at Spelman to showcase their work:

[Spelman]…[received] a Model Institute for Excellence grant…intended to build [a] “pipeline” of young women in STEM. [Some] grant funds [were used] to host…Science Day…each spring when…students in the STEM majors [had] a little conference where they presented poster…and paper presentations. [It] was…intended to encourage research on the part of our STEM majors.

Dr. Tatum also prioritized sabbaticals to relieve the physical and physiological costs of the John Henryism strategies employed, especially by STEM faculty of color, to battle racial fatigue and the emotional labor of teaching and conducting research at an HBCU (E. McGee, 2021). By operationalizing her equity ethics, Dr. Tatum meaningfully addressed the underlying issues of workload that disproportionately impact faculty of color and, by default, their students.

Discussion

The equity ethics framework is pivotal to understanding the leadership approaches of HBCU presidents. Each leader’s unique origin story unveils a distinct trajectory of experiences that shaped their leadership.

These presidents were born and raised during periods marked by Jim Crow, segregation, open racial and gender oppression, and the epochal moment when the Brown v. Board of Education decision eradicated the legal basis for racial segregation in U.S. schools. Their rich narratives encompass encounters with racial and educational injustices leading to profound paradigm shifts in their worldviews and forming the foundations of their leadership equity ethics and their understanding of the urgency of diversifying STEM.

The equity ethics of these leaders suggest that dynamism and evolution inform their perspectives, influence their decisions, direct their political capital, and shape the risks they take to broaden Black participation in STEM. This equity approach is transferrable across institutional settings and offers a holistic approach for non-HBCU institutions.

Their understanding of linked fate has empowered HBCU presidents to establish operational codes for fairness and inclusion, carving promising futures for Black students in STEM. Such codes are yet to be widely adopted despite the increasing need for competitiveness and diversity in STEM. Bold acts, such as Dr. Ernest J. Wilson III’s insistence that his faculty position be “linked” to opportunities for his students, exemplify operationalizing equity ethics. Such acts by other academic leaders could potentially transfer these ethics beyond HBCU boundaries, creating programs and institutional structures that advance Black students through STEM in all institutions.

Conclusion

HBCU leaders helm complex institutions catering to a significant portion of marginalized communities drawn to higher education by promising improved life quality. The promise and allure of STEM degrees are particularly intense for these communities. However, disenfranchisement within the U.S. higher education system often excludes members of these communities from such opportunities. HBCU leaders, guided by equity ethics, can leverage their concern for justice to challenge these trends and increase Black representation in STEM.

The equity ethics of the participants in this research are situated within the broad history of U.S. racism, their individual histories, and their responses to navigating racially charged social contexts. These leaders have intertwined the “political with the personal,” leveraging their origins to chart paths marred by injustice and disenfranchisement, thereby opening doors for Black students in STEM and giving rise to the lasting legacy of HBCUs in educating a significant proportion of Black STEM degree holders. However, due to entrenched institutional and structural racism, much still needs to be done.

Other institutions stand to benefit from examining how HBCUs, despite numerous challenges, lead the nation in educating Black students in STEM. An equity-centered approach is critical to understanding HBCU leadership and developing the know-how of HBCU leaders. The nation cannot rely on HBCUs alone to mitigate the pervasive effects of racism in STEM. Leaders across all higher education institutions, disciplinary societies, and associations are strategically placed to learn from HBCU leadership and apply these insights, values, and practices to their strategic planning, decision-making, and external relations to serve Black and other marginalized STEM students better.

Equity ethics signifies going beyond a generic menu of diversity initiatives, activities, or strategies. The HBCU presidents interviewed in this study underscore how their equity ethics inform strategies that address the underrepresentation of Black students in STEM, suggesting that the most innovative strategies emerge from those in influential positions who embody equity ethics in decision-making and solution implementation.

The findings of this study can contribute to deciphering methods and approaches leading to the disproportionate success of HBCUs in graduating Black STEM students. Equity ethics provides a universal lens for viewing the complexities of leadership and broadening participation within and beyond the HBCU context. Examining one’s equity ethics serves as a strategic starting point for any leader desiring similar outcomes at their institution. Ultimately, cultivating and developing equity ethics into a leadership platform for racial justice in STEM positions leaders and the nation for success in broadening participation and inclusivity in critical STEM fields.

Ebony McGee, Ph.D., is a Professor of Innovation and Inclusion in the STEM Ecosystem at Johns Hopkins University. An electrical engineer by training, she is a leading expert on race and structural racism in STEM and takes a critical race perspective to her work on the experiences of minoritized groups in STEM. Her work focuses on the mental health consequences of racism in STEM, and her leadership is driven by an equity ethic that challenges structural racism and advocates for mental health and wellness in the STEM ecosystem.

Kelly Mack, Ph.D., is the Vice President for Undergraduate STEM Education and Executive Director of Project Kaleidoscope at the AAC&U. She is a physiologist with extensive experience in STEM gender equity and institutional transformation. She previously served as Senior Program Director for the National Science Foundation’s ADVANCE Program and has led numerous initiatives to promote equity in STEM. She has built her leadership approach on servant leadership, emphasizing mentorship and creating inclusive higher education environments. Her extensive academic experience and advocacy for gender equity has shaped her belief that fostering equitable opportunities is essential to nurturing diverse talent across STEM.

Whitney Frierson is a doctoral candidate in the Department of Sociology at Vanderbilt University. Her research focuses on race, gender, mental health, and well-being, and the experiences of Black students in higher education. Her current work examines discrimination experienced by Black doctoral students and their unique coping strategies. She approaches leadership with a focus on the intersectionality of race, gender, and well-being, informed by her research on the experiences of Black students in higher education.

Devin White is a doctoral candidate in Education at Johns Hopkins University, where he researches barriers and supports for Black students in STEAM fields. His dissertation focuses on the experiences of Black caregivers in STEM contexts. Devin’s work is informed by critical race theory and intersectionality. His leadership is grounded in an intersectional understanding of the barriers and supports for Black students in STEAM fields.

Orlando Taylor, Ph.D. (posthumous) was a distinguished leader in higher education. He served as Dean of the Graduate School at Howard University and Vice President for Strategic Initiatives at Fielding Graduate University, where he was also Distinguished Advisor to the university’s president. He was a national advocate for diversity in STEM, particularly at HBCUs, and a pioneer in advancing equity for women and people of color in higher education. His leadership was defined by a commitment to creating pathways for underrepresented groups. His influence continues to inspire our work, guiding our mission toward more inclusive and supportive STEM education.

CASL examines historical and contemporary attitudes, behaviors, standards, and practices of HBCU leaders that lead to successful outcomes for Black STEM major students.

Research shows that input from engineering college deans is essential to reshaping university cultures and engineering education (Dalal et al., 2021; E. O. McGee et al., 2021).